Nigeria: Who Pays Back Nigeria’s Debts?

By Nosa James-Igbinadolor

Once again, Nigeria has a debt problem. Fourteen years after former President Olusegun Obasanjo and his economic team led the country to exit the debt trap of the 1980 and 1990s, Nigeria is once again wallowing in a second debt trap with absolutely no idea of how to exit. Nosa James-Igbinadolor looks at how and why Nigeria got there.

There was a time when Nigeria was relatively free of foreign debts. Looking back now, one would be hard-pressed to remember those halcyon years of relatively good economic management under former President Olusegun Obasanjo driven by an erudite economic team led by Dr Ngozi Okojo Iweala, but, the government paid back Nigeria’s debts.

“Nigeria will not owe anybody in the Paris Club one kobo,” the President Olusegun Obasanjo had said in a statement after Nigeria paid a final installment of $4.5 billion to the Paris Club of creditors in a deal that allowed the country to pay off about $30 billion in accumulated debt for about $12 billion, an overall discount of about 60 per cent. The country committed to using foreign reserves, salted away as oil prices soared, to cancel its debt, which had been racked up during decades of military rule.

Debt relief championed by the former President had become a central issue in the fight against poverty. Nigeria, which owed about $36 billion in overall debt, was at that time, one of the most indebted nations in the world. But we did pay back in 2006 and ended the debt trap, with just a little over $3 billion hovering around as external debt.

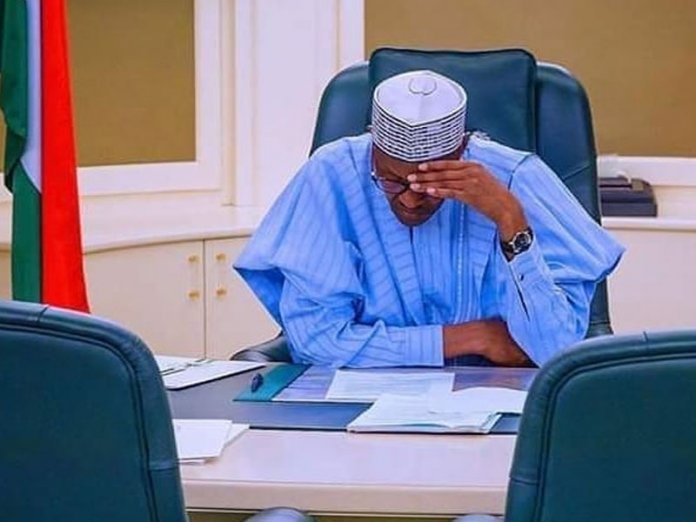

That was until 2015 when President Muhammadu Buhari assumed office. According to statistics published in March 2020 by the Debt Management Office (DMO), Nigeria’s total external debt stock as at December 2019, stood at $27.676 billion. In May 2015, when the President took office, the total debt profile of the country stood at $10.316 billion. Thus, in less than five years, the country’s debt has tripled in size with little to show for it except higher spending on recurrent expenditure, limited capital expenditure and a lot of stolen wealth.

Ike Brannon, a Senior Fellow with the Jack Kemp Foundation, in a 2019 analysis for Forbes, posited that “Nigeria’s biggest economic problem, though – and the issue that requires real political acceptance from Buhari’s government – is the country’s growing public debt. Since assuming office in 2015 President Buhari’s government has added considerably to the nation’s debt, which now exceeds $85 billion. In essence, the nation’s debt is about where it was in 2005-06, just before Nigeria benefited from massive debt relief as part of a program coordinated by the Paris Club, IMF, World Bank and the African Development Bank. To have squandered the debt reduction in just 14 years and have no tangible economic progress to show for it is beyond disappointing.”

Nigeria’s Eurobonds accounted for $10.86 billion or 39 per cent of external debt as at April 7, 2020. The country paid $771 million in interest on its Eurobonds last year compared with $329 million in debt service to multilateral creditors, according to the DMO. Total borrowings from China as at March 31, 2020 stood at $3.121 billion, which the DMO asserts to be concessional loans with interest rates of 2.50 per cent per annum, 20 years tenor and seven years grace period (moratorium).

“The $3.121 billion loans are project-tied loans. The projects (eleven – 11 in number as at March 31, 2020), include: Nigerian Railway Modernisation Project (Idu-Kaduna section), Abuja Light Rail Project, Nigerian Four Airport Terminals Expansion Project (Abuja, Kano, Lagos and Port Harcourt), Nigerian Railway Modernisation Project (Lagos-Ibadan section) and rehabilitation and upgrading of Abuja-Keffi-Makurdi Road Project,” the agency stated.

According to DMO, the impact of these loans is not only evident but visible, adding for instance, that the Idu-Kaduna rail line has become a major source of transportation between Abuja and Kaduna.

According to a November 2019 report by PwC Nigeria, “the widening budget deficit necessitates the government’s resolve to borrow to cover its revenue shortfalls. The government has reiterated that the existing debt level has not breached the internationally acceptable threshold of 30% debt-to-GDP ratio. As of 2018, the federal government’s total debt stock stood at N20.5 trillion, a 12% increase from N18.4 billion in 2017.

Consequently, debt-to-GDP rose to 29% from 27% recorded in the prior year. By H1 2019, the debt-to-GDP ratio surged to 61%. With a slowing economic growth rate and a spiraling debt growth rate, the debt-to-GDP ratio may pass the 30% threshold by year end 2019. However, the debt-to-GDP ratio paints just half of the picture. The issue bordering on debt sustainability is the ratio of debt service to government revenue on one hand, and the ratio of government debt to government revenue. Since 2011, debt service-to-revenue ratio rose consistently from 21.2% to 51.9% in 2015 peaking at 86.6% in 2016. It declined thereafter to 78.6% and 67.7% in 2017 and 2018 respectively. This significantly exceeds the international acceptable threshold of 20 – 25%. The continuous decrease in debt service-to-revenue ratio over the last two years is underpinned on revenue growth which outpaced growth in debt servicing within the period under review”.

In the 2019 budget, an elephantine N2.140 trillion was set aside to settle debt obligations, indicating that about a quarter of the budget provision for that fiscal year went to debt repayment. This moved up by N130 billion when compared with the N2.010 trillion that supposedly went into debt servicing in the 2018 fiscal year.

According to PwC, despite sluggish output growth recovery, low domestic revenue mobilization and the unsustainability of the current debt level, the government intends to borrow more to plug the revenue shortfall of N2.2 trillion in the proposed 2020 budget.

What this simply means is that the federal government, faced with heavily depreciating income from crude, will have to borrow to pay interests on its external debt.

The spiking cost of Nigeria’s debt profile reached a new high with the country’s debt service as a percentage of revenue rising to 99% in the first quarter of 2020. Figures contained in the Medium-Term Expenditure Framework and Fiscal Strategy (MTEF/FSP) report released recently by the Federal Ministry of Finance, Budget, and National Planning show that in Q1 2020, the country chalked up a total sum of N943.12 billion in debt service while the federal government retained revenue was put at N950.56 billion, implying Nigeria’s debt service to revenue estimate to be 99% during the period. This is the highest on record and posits that virtually all the revenue generated from both oil and non-oil sources was used to meet debt service obligations.

The growing debt profiles of the federal and sub-national governments continue to raise concerns among policymakers and analysts. From within the government, Central Bank Governor, Godwin Emefiele, had in a January 2019 Monetary Policy Committee meeting cautioned the Federal Government against Nigeria’s rising debts profile. Emefiele said the country’s debts profile is alarming. According to the CBN Governor, “On external borrowing, the committee noted the increase in debt level advising for caution, noting that it could fast be approaching the pre-2005 Paris Club level.”

An economist, Mr. Bismarck Rewane, who is the CEO of Financial Derivatives Company (FDC) and member of the Federal Government’s Economic Advisory Council constituted by President Muhammadu Buhari, together with other analysts in the FDC, warned in their bi-monthly economic update in January that the country’s debt had grown by 214.90 per cent over the past six years, from N8.32trillion in June 2013 to N26.2trillion as of September 2019. “It is vital to employ proactive measures to reduce the current debt level,” they said.

The report added that, “as a result, the ever-increasing government spending is yet to yield any notable results; poverty is on the rise and health and educational facilities remain inadequate amid the fast-growing population. Debt service has become a significant portion of the expected revenue in 2020. It accounted for over 60 per cent of the government’s independent revenue in 2019.

“The total debt has been increasing ($85.39billion) but total factor productivity growth has been declining (-0.4 per cent). This implies that the FG borrowings are hardly used for productive purposes. The debt service, after a while, becomes a burden on the government and its fiscal balance.”

“Nigeria’s mounting debt profile is a major concern despite the country having about $900bilion worth of dead capital in properties and agricultural lands (PwC Nigeria, 2019),” the Nigerian Economic Summit Group, a private sector-led think-tank, also warned in its 2020 Macroeconomic Outlook.

Financial resource firm, nairametrics notes that, “Most of these debts were borrowed in the first four years of the President Muhammadu Buhari’s administration via multilateral, development, bilateral and commercial loans (Eurobonds and Diaspora bonds). The government claims it had no choice, seeing its oil revenues failed to meet up with the target and thus is unable to fund Nigeria’s huge infrastructural deficit required to propel economic growth.”

It was former vice-president Atiku Abubakar’s intervention earlier this month that raised the tempo in the discussion and analysis of the country’s unbridled debt acquisition non-strategy. He had warned in a statement he personally signed that Nigeria’s increasing debt profile, which stood at 99 percent of the nation’s revenue profile in the first quarter of 2020, would drive the country towards economic precipices. “Nothing has shocked me in my entire life in public service as the revelation from Nigeria’s First Quarter 2020 financial reports in the Medium Term Expenditure Framework and Fiscal Strategy from the Federal Ministry of Finance, Budget, and National Planning, which shows, alarmingly, that whereas Nigeria spent a total sum of #943.12 billion in debt servicing, the federal government’s retained revenue for the same period were only #950.56 billion.

“This means that Nigeria’s debt to revenue ratio is now 99 per cent. This is a crisis! Debt servicing does not equate to debt repayment. The reality is that Nigeria is paying only the minimum payment to cover our interest charges. The principal remains untouched and is possibly growing.”

In order to hide the depressing reality of the debt problem, debt-to-GDP, which is not regarded as the best indicator of debt sustainability, especially in a country where tax-to-GDP is low, is now widely touted by government officials including the DMO to explain away the deepening malaise.

As noted by nairametrics, “Oftentimes, the government discards the debt servicing to revenue ratio and instead, adopts the debt to GDP ratio to dissuade concerns on growing indebtedness. They persuade citizens with the narrative that Nigeria’s debt portfolio currently stands at 19.03% of the GDP and still below the 25% threshold set by the government on medium-term 2018-2020, insisting that there is no cause for alarm.

“But that logic seems to be a clever approach to dodge genuine concerns. The simple truth is that, as long as the country’s debt mount, so would revenue prospect slump and the unborn generation would be thrown into an uncertain financial situation. Already, the effect of past debt binge is limiting revenue availability and this is obvious from the N1.859 trillion deficit in the 2019 budget proposal, which the Debt Management Office (DMO) had hinted would be sourced from external loans.

“With the worrisome trajectory of debt, it seems Nigeria has failed to draw from the hard lesson of the pre-2005 debt crisis”.

Mr. Egie Akpata, Ag. MD/CEO of UCML Capital Ltd, told THISDAY earlier in the year that, “If you use the bulk of your money to pay off debts, then it is because you owe too much. There is no need talking about countries that have high debt to GDP and low borrowing costs. If you go to Japan, where the debt to GDP is about 140 per cent, the government just like many countries in Europe can borrow money at literally zero per cent. So if the Nigerian government can borrow 30-year money at zero per cent, then you would have technically, a very low debt servicing.

“We have to understand that the countries that DMO try to compare us within their documents have high revenue to GDP. You can’t have low revenue to GDP and expect to have high debt-servicing problems, the type Nigeria has. Secondly, these countries tend to owe almost all their debts in local currencies. I am not aware that the U.S government has material debts in foreign currencies, same for Canada, same for U.K. Most of these countries owe almost all their debts in their local currencies. We are at the opposite end and that is why we have constraints. These constraints are the outcome of our poor foreign currency earnings.

While the debt level has sparked fears that the country is heading towards a crisis, the reality is that debt itself is not a problem as long as it can be transferred into valuable and productive assets. The problem has been how the country has invested the tens of billions of dollars it has borrowed under this government. With an unalluring business environment unable to attract FDIs and interest rates too high to stimulate investments, the Buhari administration’s economic management strategy leaves little room for credible and sustainable economic growth to take place, thus deepening the country’s debt challenge.

The IMF has at varied times warned the Nigerian government that continued foreign-exchange restrictions are among the factors that dampen long-term foreign and domestic investment and keep the economy reliant on volatile oil prices, arguing that the elimination of exchange-rate restrictions and multiple-currency practices would “remove distortions and help economic diversification.”

In addition, Nigeria’s debt management strategies are not properly aligned with the country’s financial capacity. For example, while most developing countries take advantage of concessionary financing from the World Bank or other international institutions, Nigeria’s debt profile is now increasingly made up of commercial debt. Its recent Eurobond issuances in London, for example, came at a relatively high yield, which makes its economy especially vulnerable to external shocks, such as a sustained drop in oil prices.

The IMF agrees that African countries have been on a Eurobond issuing spree with half of them being near or at distressed levels. The fund posits that African governments are piling on debt without evaluating the exchange rate risks and the real costs of repaying the debts.

No doubt, one of the most significant challenges facing the country at this stage is the absence of operational independence by the DMO, the agency set up to coordinate the management of the country’s debt. The DMO is expected to be separate from the Ministry of Finance and from monetary policy as well as autonomous from political influence. However, that independence is suspect as there is strong evidence of political interference in the coordination and management of the country’s debt.

In addition, important economic decisions regarding whether to borrow, where to borrow and how to borrow have become political decisions fundamentally taken outside the advice of responsible institutions including the Ministry of Finance and the DMO. This leaves the country working asymmetrically information wise and operationally when best judgement is dismissed for political expediency.

What is clear is that unless there is a rethink of the way Nigeria borrow and why she borrow, the country would face an existential debt problem that would leave no room for infrastructure-driven development in the next few years